Regardless of where you are in the military, an Executive Officer (XO) is an organization’s principal administrative taskmaster. The organization, or command, will generate many tasks internally, but it will also receive tasks from the Immediate Superior in Command (ISIC—such as an air group or a ship’s parent squadron) and other external organizations that should not have the power to directly assign tasking but often do. Here, tasks don’t mean operational orders like “go here, blow that up,” but administrative ones like “review your command’s motorcycle safety program and report compliance.” The XO’s job is to catch these tasks as they come in, quickly define them, prioritize them, assign them to the right person, and track them until they’re done. Naturally, email is at the center of it all.

This post describes an inbox management “system” which you are guaranteed not to use. There are as many inbox management systems as there are users of inboxes; nobody does it quite the same way or follows any “system” strictly, and nobody’s “own way of doing it” works forever. Especially for Executive Officers aboard seagoing commands, E-mail inflows oscillate with the deployment cycle, ramping up as we prepare for inspections, tapering off as we enter EMCON, and changing shape as the ship and ISICs bring in new personnel with new email habits. What this post can do for you, then, is give you ideas, describing in detail a system that worked for one fairly typical XO, most of the time. Regardless of your commitment to follow someone else’s recipe, mine or any other, you will do your own thing in the end.

INBOX ZERO and GTD

First, I want to touch on a couple of popular “inbox management systems,” if only because you’re likely to hear them recommended at some point. I have to qualify this upfront by stating clearly that I have not found either to be particularly life-changing, and I think it’s both funny and depressing that bestselling books have been written about how to file emails. In any event, there are useful takeaways from each, and there’s value in just being by-name familiar with these “systems” before somebody recommends them to you.

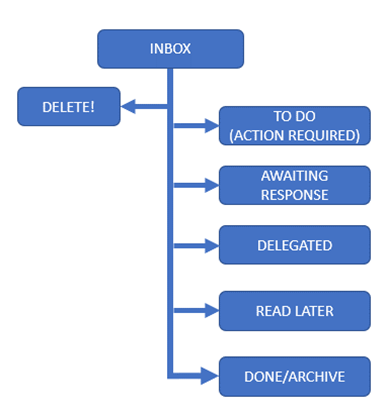

The first is the “Inbox Zero” method originally described by blogger Merlin Mann. First a series of popular blog articles at 43 Folders, then ultimately a book, Inbox Zero is less a “system” and more a “work philosophy” built around keeping an itchy trigger finger near the delete key. To the extent that it even merits a flow chart, my completely-made-up version of one is shown here, however, the earth-shattering innovation that emails can be filed into sub-folders isn’t really the point of Inbox Zero. The point is that a clear inbox, kept that way by aggressively deleting the nonessential and giving the rest a bare minimum of your time, can ostensibly lead to a blissful reduction in stress and improvement in mental clarity. The “how,” isn’t really that important; just keep the damned inbox empty and accept that it will change your life. Or something like that.

The second approach you should be aware of is David Allen’s “Getting Things Done” method, sometimes imaginatively abbreviated “GTD.” This approach is less explicitly about email management and is instead supposed to be about “tasks,” and the GTD could theoretically apply just as well to reviewing physical admin or making phone calls as it does to managing an email queue. Unlike with Inbox Zero, a flow chart is actually necessary, as there is quite a bit more substance to this approach. The book is worthwhile, but you can glean about a 90% understanding of the “system” just by looking at a flow chart.

Strictly concerning email management, I think there are a couple of useful takeaways from GTD. The first is that if a task takes less than two minutes (such as a quick reply or phone call), you just do it. Doing it then and there, with no consideration of where the task falls out in order of priority, simply gets it off the plate and out of the way. The reduction in the total number of outstanding tasks is worth the possibility that you might have spent two minutes doing a less important thing which you otherwise would still eventually have got around to anyway.

The second big takeaway, for me, is the general principle that every task (or email, in this case) belongs somewhere, and that there should be no ambiguity about where it goes. David Allen swears that he never has to think about what to do next; his process tells him what to do, with minimal time wasted in deliberation. An email is either actionable or it’s not, and if it’s not, you either need to keep it around for future reference or you get rid of it. No need to hem and haw while it sits there in your inbox, stressing you out. For actionable emails, if it’s got multiple steps, then it is a project you need to assign to somebody. If it’s got one step, you either do it, assign it, or schedule it on the calendar. It does not just linger the inbox until you are forced to confront it.

I read Getting Things Done during the Submarine Command Course, enroute my tour as an Executive Officer. Steeling myself to become the best XO the Navy has ever seen, I took detailed notes, sketched out my own anticipated workflows, adapted GTD to what I imagined my job as an XO would be. Of course, all this effort was laughably naïve, and my immaculate plan collapsed after about thirty seconds of the day-to-day crisis management that is being an Executive Officer. The “tasks” are just too varied, with too wide a spectrum of priority and coming from too many directions to simply snap on somebody else’s process. You’ve got message traffic, you’ve got CO bolts-out-of-the-blue, you’ve got day-to-day crises and fires that need putting out. Some of them are actual no-kidding fires.

The fundamental reason popular systems like GTD cannot work as-designed for a Navy XO is that your tasks don’t just come via email, and you don’t (you had better not!) spend all day sitting in front of a computer. Everyone’s brain works differently, but my mental organization system bins task-flows into one of three “hubs”: the electronic inbox, which this article is about; the physical inbox, because we will never ever outgrow paper and should stop lying about it; and the physical planner I carry around, from which I write down or assign tasks during meetings and presentations. If a task is tracked in one of these, I should not recreate it in another—provided that I am disciplined about keeping the tasks moving. An inbox stuffed with languishing admin is a no-no.

Even if it was naïve, my planning effort during the command course was far from wasted. Plans are useless but planning is indispensable, and all that. Thinking through both the GTD method and the Inbox Zero philosophy left me with some essential principles that remain a part of my day-to-day workflow. Do the quick tasks quickly to get them out of the way. Have a system that gets everything assigned and tracked immediately, with minimal expenditure of mental energy. Keep the inbox empty, especially of unassigned tasks. And with those principles as a bedrock, on to what I do.

What I Do: The File Dump

Central to my method is the PST. Also known as an Outlook Data File, a PST is a single file that can contain an unlimited number of Outlook emails saved directly into a file on the sharedrive, instead of taking up space on the Exchange Server. Within Outlook, it just looks like another folder. The most immediate benefit of using a PST is that you stop getting “your inbox is out of space” messages. The Outlook Data File ends in the extension *.pst, which stands for “personal storage table.” Everyone I know who uses it just calls it a “PST.”

As of 2025, in its increasingly aggressive campaign to upsell its clients on cloud services, Microsoft is phasing out the ability to generate PSTs. This obviously won’t work on warships, which frequently operate without connectivity to, well, anything, but I imagine some smart person will figure out a way to create a virtual cloud within a ship’s infrastructure. In any event, if you’re working with a version of Outlook that doesn’t permit the creation of PSTs, then you can just use an internal folder for essentially the same purpose.

In the version of Outlook that I’m using, I create a PST by clicking “Additional Items” -> “Outlook Data File.” The exact clicks to get there are likely to change as the software evolves. Ensure you pay attention to where you put the actual PST file; you’ll want to put it somewhere other than Outlook’s default choice.

Once a week, in what I call the weekly consolidation, I move all the emails remaining in my inbox to the PST. Most of these could just be deleted, but that would require a time-consuming decision for each email. Even if would just take a few seconds for each, dumping the emails to a PST is considerably faster than thinking over each one to decide whether I might need it someday. Instead, I decide which sub-folder of the PST it belongs to (more on that in a moment), and most importantly, whether or not I still have some outstanding action from the email. With every weekly consolidation, I find several items that merit follow-up with a Department Head (DH) as well as one or two minor tasks I would have otherwise dropped entirely. I normally do this routine on Thursday afternoon, so I’ve at least got Friday to run down anything requiring a follow-up.

As you might expect, the PST can get quite large, into the hundreds of MB. I keep this manageable by starting over with a new PST every few months, particularly when the ship enters a new phase such as a deployment or a major maintenance availability. On the rare occasions where I need to dig up an old email conversation, it’s much easier to remember that it occurred during “Patrol 104” than to remember that it happened in May. To minimize antagonism to my IT organization, I thin out the archived PSTs by sorting the sub-folders by size and clearing out the largest emails excepting the absolutely essential. At the end of a tour, I delete all archived PSTs along with the years’-worth of schlock accumulated in my personal sub-folders.

Don’t forget to PST-dump your own sent emails, as these will also eat up your inbox space and are frequently needed for future reference. Also, ensure you keep the PST in a restricted folder, because anyone who can access it can also access all of its contents. Theoretically, you could use a PST to turn over your email history and Outlook task list to your relief at the end of your tour… but I wouldn’t bother, because they’re not going to use it anyway.

Do NOT PST-dump any email that you have flagged as a task / follow-up in Outlook. Once it goes from your inbox into the PST, it ceases to show up on your Outlook task list even if it was flagged. More on that in a bit.

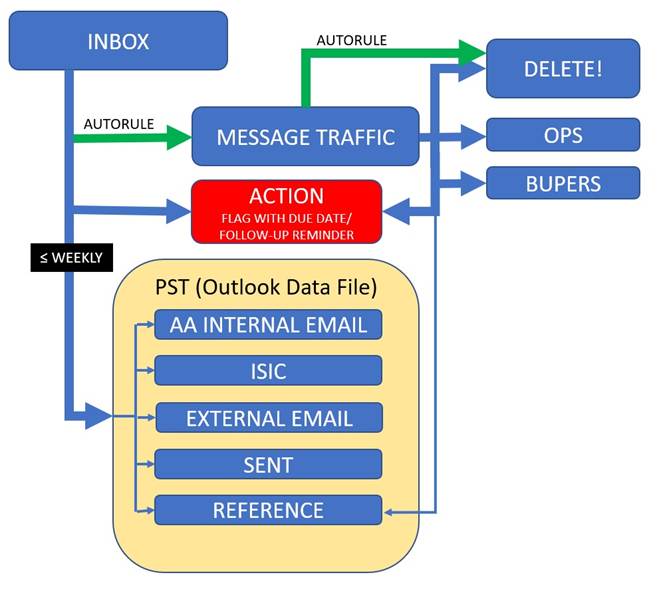

Rules and Message Traffic

I am a minimalist when it comes to Outlook “rules” for automatic filing, as well as for the creation of sub-folders. I find that both of these features tend to run amok, contributing to lost emails and dropped tasking. One place where rules are absolutely necessary, though, is in dealing with Naval message traffic. I set up a rule that funnels all message traffic into its own folder, and another rule that auto-deletes the clearly-identifiable spam. I am fairly stingy with this rule, having been burned too many times by missing something important which was auto-deleted by a well-intentioned rule. Unlike interpersonal email, I am content to manually delete most message traffic after giving it a microsecond-long glance. I can always get it back if needed, either from Radio or WAMR.

Most of my daily message traffic review is spent tapping the “delete” key, consistent with the Inbox Zero philosophy. I clear out the message traffic folder every day. While at sea or preparing for underway, I file all operationally-significant traffic (OPSKEDs, movement messages, etc) into an “Ops” sub folder, and I always file BUPERS traffic into a “BUPERS” folder. I could easily set up rules to automatically file these, but forcing myself to put eyes on each message ensures that I stay abreast of their contents. This isn’t to do redundant work with any of my team who actively deal with these messages, but to catch the surprises early and get people moving quickly when necessary.

For messages that I may want to keep around indefinitely, such as a “lessons learned” message, then it goes directly into a REFERENCE sub-folder in the PST. If it’s something I need to track for action, such as a directed mandatory training-du-jour, then it gets assigned, flagged for follow-up, and moved to an ACTION folder, NOT in the PST. If it went into the PST, it would cease to show as a flagged item in the task list.

Because message traffic naturally displays differently than email, I have found it worthwhile to screw around with display options for the Message Traffic folder. Right-click at in the bar at the top of the folder where it says “All,” “Unread,” etc. At the bottom of the window that popped up, click View Settings, then in the next popup (which should say Advanced View Settings at the top), click Columns. Here you can specify which “columns” are previewed; I show Flag Status, Attachment, Subject, Received, Size, and Categories. The main benefit of this effort is getting the “SUBJ” line from the naval message to display prominently in the folder preview. I also recommend that you go to Other Settings in the Advanced View Settings window and disable Automatic Column sizing.

Folders

My PST is divided into a small number of sub-folders. At the top of the list is “AA Internal Email”, prefixed with “AA” so that it stays at the top of the alphabetized list of folders. This is where the mass of emails internal to the ship go, and it is by far the largest folder. Any email from any entity outside the ship goes into the “External Email” folder, except for those from my parent squadron, which go into the “ISIC” folder. There are an infinite number of customization options you might consider; friends of mine do things like conditional formatting for emails from bosses, creating special subfolders for every possible sender, or using rules to separate emails in which they are a direct addressee from those in which they were merely CC’ed. Having tried all of these practices, I’ve found none of them to be particularly useful, and aside from the indulgence of a special “ISIC” folder I strive to minimize the creation of sub-folders and special categories. In my experience, any overlaps in the Venn Diagram of “where an email could be filed” create opportunities for emails to get lost in a maze of folders and never to be seen again.

Tracking Follow-Ups

All items flagged/tracked for action go into the ACTION folder, again, NOT in the PST. Almost everything in here should have been tasked out to someone else, however, these items remain my problem to track until the tasks are completed. There are numerous ways to make Outlook remind you of these pending follow-ups; here are a few that I’ve used.

My preferred method is to simply track the sent email as a task. The easiest way to do this is to go to your SENT folder and drag the email down to the “tasks” button at the bottom of outlook. This will create a new Outlook task named with the subject line of the sent email, and you can set a due date for whenever you desire to follow up. The task will sit there patiently in your Outlook task list (some people call this a “tickler,” but I refuse) until it comes due, at which point it turns red. A disadvantage of this method is that it can crowd out the task list and obscure more important reminders, but I’ve never personally found this to be a problem. Because I don’t use Outlook’s task list for recurring admin, mine tends to stay pretty thin.

Another method is to simply send a timed email to yourself. For example, say you emailed a task to someone with a 48-hour deadline. You can go to your “sent” messages, forward a copy of your tasking message back to yourself with a delay set for 72 hours. The email will sit in your outbox until the 72-hour point, after which it will pop into your inbox as a very visible reminder that three days ago you told somebody to do something. If they did it, you can simply delete this reminder email; if not, you can forward it (with genuine or contrived annoyance, as appropriate) to the previously-tasked individual to demand a follow-up. I don’t prefer this method because seeing a little [1] next to my outbox is annoying, but it has some advantages: it does not crowd up your task list, and receiving an email from yourself may be more likely to force the desired response than another overdue Outlook task.

Make Your Own System

Like I said at the beginning; what’s described here is a system you are guaranteed not to use. I hope it gave you some ideas. As you develop and refine your own “system” of inbox management, I urge you to continuously experiment. Don’t fret and fuss too much about adherence to any particular prescribed system; you’ve got enough stress without the self-inflicted variety. There are no points for adhering to some prescription that doesn’t really work for you. What matters, more than anything else, is that the tasks get done.

Leave a comment